WHAT IS THE SCIENCE OF READING?

Bridging the science to the parent.

We’re not sure about you, but all the science talk and jargon about how we learn to read can get a little overwhelming and confusing – especially if you’re trying to connect the dots to the right terminology, not to mention all the different charts that are used to demonstrate the Science of Reading, Structured Literacy and how we process the information in our brains.

What we have tried to do in this section is to break down what we have learned from the Science of Reading research, what needs to be taught and how the brain processes the information.

We think it’s important to clarify first what the Science of Reading is and what it is not, as there can be some confusion around this.

The Science of Reading is:

- The Science of Reading is a large collection of scientifically based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing.

- This research has been conducted over the last five decades across the world, and it has come from thousands of studies conducted in multiple languages.

- The Science of Reading has formed a vast amount of evidence to inform how proficient reading and writing develops.

- The Science of Reading tells us why some have difficulty.

- The Science of Reading tells us how we can effectively assess and teach to improve student outcomes through prevention and intervention for reading difficulties.

- The Science of Reading comes from many researchers from multiple fields: cognitive psychology, communication sciences, developmental psychology, education, implementation science, linguistics, neuroscience and school psychology.

It is also important to understand what the Science of Reading is not:

- The Science of Reading is not a programme of instruction.

- The Science of Reading is not a single component of instruction such as phonics.

- The Science of Reading is not an ideology, philosophy or one person’s idea of how we learn to read.

- The Science of Reading is not a fad, trend or new idea.

- The Science of Reading is not a political agenda.

What have we learnt about the Science of Reading?

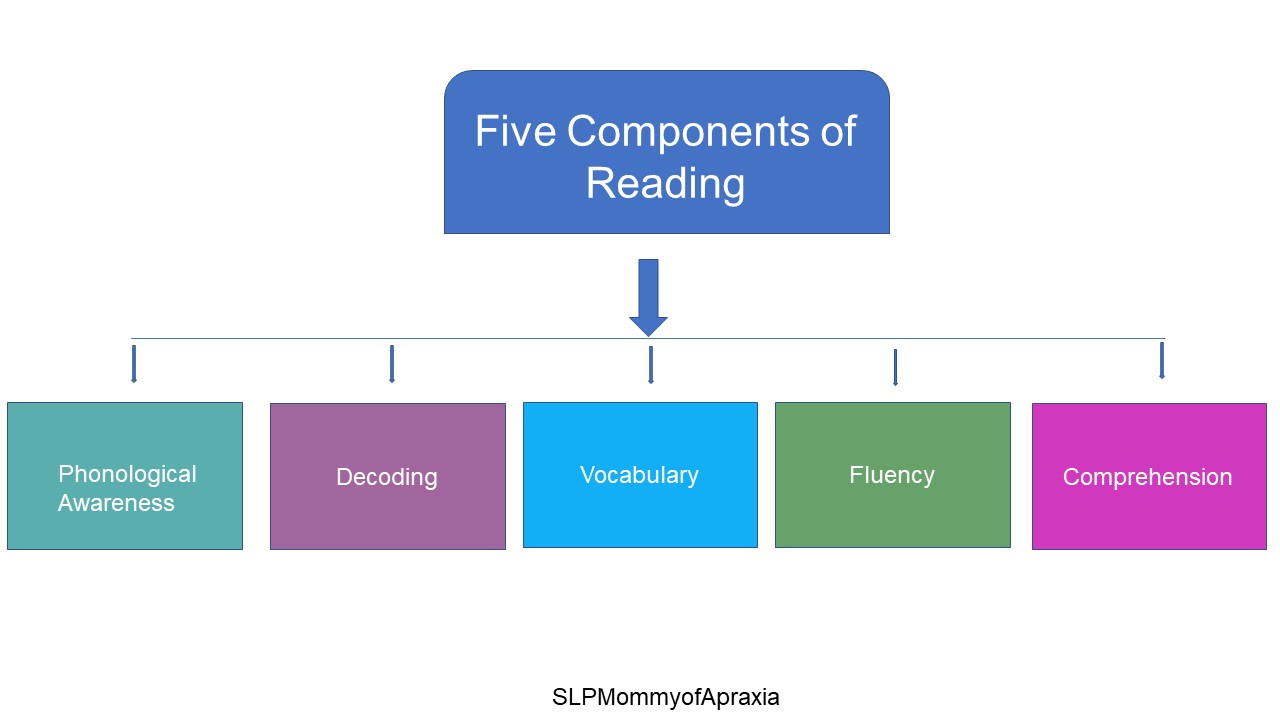

What we have learnt from the 1,000’s of research studies is that essentially all brains learn to read the same way and that includes our dyslexic children. This can be quite surprising to many, but it is true and we have the evidence to back it up. We also learnt that to be a good/skilled reader, you NEED to be taught using what is referenced as the ‘Big 5’ by the National Reading Panel report (2020) which is also part of the research called the Science of Reading. If you would like to learn more please check out the Research section of this website.

The ‘Big 5’ as we will refer to them in this section, are the five essential components of reading:

Phonemic awareness: Phonemic awareness is awareness of the smallest units of sound in spoken words (phonemes) and the ability to manipulate those sounds. Phonemic awareness falls under the category of phonological awareness, which includes the understanding of broader categories of sounds, including words, syllables, and onsets and rimes.

Alphabetic Principle: Alphabetic Principle is having an understanding of the skills to match the letter to sound and sound to letter to use in reading (decoding) and spelling (encoding). Also known as symbol to sound and sound to symbol.

Fluent text (phrases and sentences) reading: Fluency is reading with accuracy, appropriate rate (speed), and prosody (expression).

Vocabulary: Vocabulary is the understanding of words and word meanings.

Comprehension: Comprehension is the understanding of what we read and is the ultimate goal of reading.

The Learning Journey

The journey to comprehension can be a long journey for dyslexic children and children who may struggle for other reasons. What we do know is with the right intervention and approaches in place, all dyslexic children and adults can learn to read. Firstly, it’s important to understand where the difficulty begins with a dyslexic learner. Often phonological awareness, and the alphabetic principle is where dyslexics struggle most and would be your starting point to work towards comprehension.

It is important to note the final destination is comprehension (make meaning), but you do have a few stops along the way. You will need to revisit all the components to make sure the skills are mastered before a child can become a good/skilled reader. The journey won’t go in a straight line. It is helpful to understand that each component supports and complements the other in each direction to strengthen the skill being mastered. It’s also important to understand that for some children the journey will take much longer, and they will need significantly more explicit teaching and review.

Children who struggle significantly more with phonological awareness, alphabetic principle and fluency would normally be our dyslexic children. For those who only struggle significantly with vocabulary and comprehension we would say this was a language issue and possibly a Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). It’s also important to note some children could struggle with all five components because they haven’t mastered phonological awareness, alphabetic principle, and fluency which affects vocabulary and comprehension. If you can’t read, you can’t access the school curriculum and the longer this happens the bigger these gaps become.

This is called the Matthew Effect (Stanovich).

“In the educational community, the “Matthew Effect” refers to the idea that, in reading (as in other areas of life), the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. When children fail at early reading and writing, they begin to dislike reading. They read less than their classmates who are stronger readers. Good readers read more, become better readers, and learn more words; poor readers read less, become poorer readers, and learn fewer words. In other words, if students with dyslexia read less and comprehend less, their vocabulary will not grow adequately. This has devastating consequences across the curriculum and limits secondary school opportunities.”

From this we can see that it is so important to determine where your child’s gaps are in relation to the five components and how to go about strengthening these areas.

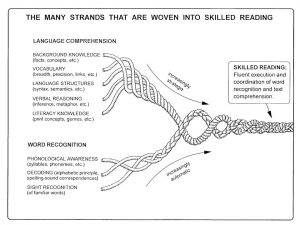

The Reading Rope (Scarborough, 2001)

The Reading Rope was created by Hollis Scarborough, and it breaks down the five components of reading into the individual skills that need to be mastered to become skilled readers. The strands are woven together, and this is important because you need all those strands to combine to become a skilled reader.

This may look scary when you first look at it but it is important. We need to bring teachers, educators, school supports and anyone else working with your child together for your child to be a good/skilled reader. We do this by teaching the strands to build a rope.

To start the process and determine what part of the rope to begin to focus on for your child, we recommend taking a look at the ‘IEP plan and School Discussion‘ section of the website.

Looking at the Lower Reading Rope – the Word-Recognition Strands you can see phonological awareness and the alphabetic principle work together and towards word recognition becoming increasingly automatic to support fluency in reading phrases and sentences. The bottom part of the rope covers three of the five components highlighted by the studies of the Science of Reading – Phonological Awareness, Alphabetic Principle and Fluency.

Lower Reading Rope: Word Recognition

Phonological Awareness is a set of skills that includes identifying and manipulating units of speech such as words, syllables, onsets, and rimes. Phonemic Awareness is the essential skill of phonological awareness you need to be a skilled reader. Phonemic awareness is where many dyslexics struggle.

Decoding is what we do when we are reading. We use the knowledge of letters that we match to the sound (Alphabetic Principle) to correctly pronounce and read the written words. Once we have mapped the words they become automatic.

Sight Recognition is our sight word memory which is also referred to as our Orthographic Lexicon or letterbox. This is where we store all the words we can read accurately and effortlessly. Literate adults have on average a sight word memory of 30,000 to 70,000 words. Starting in 4th year, it is estimated that ‘skilled orthographic mappers – good readers’ map around 10 to 15 new words a day. That’s a new word every 90 minutes! Sight word recognition is essential to become fluent at reading.

An example of the above would be: Your child is learning the sounds of the alphabet. They begin with learning the first 5 sounds of the scope and sequence you or the school are working through e.g s, a, t, p and m. They would be taught the 5 sounds /s/a/t/p/m/. The child learns to blend these sounds together to make a word they can read like ‘sat’ (decode) and then spell (encode). We repeatedly review to build automaticity to make this information get to the sight word memory and it stays there because your child has finally mastered it.

The next time they see the word, they don’t sound out s /a /t/ they say ‘sat’ because they have mapped the word and they recognise it straight away. This is when they are reading the words automatically which you will see as ‘increasingly automatic’ under where the lower strands are beginning to be woven into a rope. When they read a word automatically this helps improve fluency because they instantly recognise the word in a sentence, and they can now focus on the meaning and expression rather than sounding out.

Upper Reading Rope: Language Comprehension

Looking at the Upper Reading Rope – the Language Comprehension Strands are using the other two components from the five components highlighted by the studies of the Science of Reading – Vocabulary and Comprehension. These components have been divided into more subskills on the Reading Rope.

Background Knowledge is when your child uses the knowledge they have already, using facts or ideas they already know, to help understand the meaning of the word or sentence. This can also be referred to as world knowledge. This is why you will often hear that reading to your child is crucial – having even a little knowledge helps. Knowledge needs something to stick to and build on. If there is nothing to stick to it just floats and goes. It’s like Lego – you need one brick to start building a tower.

Knowledge is the same – you just need to start building knowledge which supports reading, writing, spelling, and comprehension. You can do this by reading books to your child, but you can also do this in everyday life at home. Something comes on the news, have a chat about it. When you watch a movie, discuss it. Let them watch documentaries and show them how knowing something in one subject can be used to help understand another.

As an example – learning about Christopher Columbus arriving in America has many connections to Captain Cook arriving in New Zealand. Help them make connections to situations or stories they know.

Vocabulary is when a child needs to understand what a word means to be able to understand what they are reading. Building your child’s vocabulary knowledge helps with their background knowledge and supports their reading and writing and comprehension.

There are many ways you can build vocabulary. Best practice is building connections to the words. What other words mean the same? Can they be put in a sentence? Draw a picture. The more connections and reviews you do, the better the chances are of getting into long term memory. See ‘Free Resources‘ to access a free vocabulary mat to help build connections and to support moving words to the long-term memory and ‘How to build background knowledge and vocabulary‘ document under the Learning Hub.

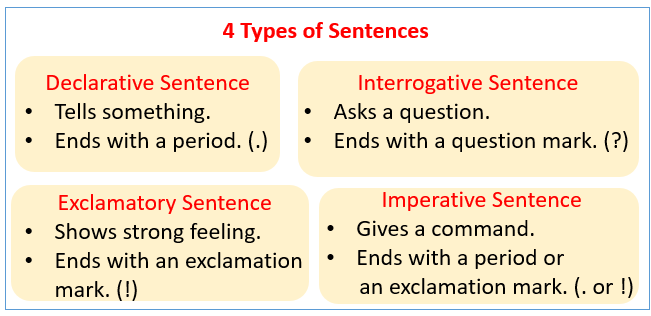

Language Structures (syntax, semantic)

- Syntax is the arrangement of words in a phrase or sentence. The English language, like all languages, has patterns and rules to follow, a way we order our words. This can also be called grammar.

- Semantics is the study of meanings of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences. Knowledge of the meaning of a text is essential to reading.

We have added some examples. Your child needs to understand the order we write by understanding parts of speech – nouns, adverbs, adjectives and grammar and understand the who, what, where, and when in story retell and in writing and they also need to understand sentence types.

Verbal Reasoning (inferences and metaphors) is the ability to understand what you read or hear. It includes drawing conclusions from limited information and developing an understanding of how new ideas connect to what you already know. An example: When hearing or reading a story, your child needs to use verbal reasoning skills to understand things like, ‘It’s raining cats and dogs outside,’ would mean ‘It’s raining heavily outside.’ because the next sentence is ‘Dad said he got wet.’ It’s about using the information you have to work out the information you don’t have. This is also called inferring or learning to use inference.

Literacy Knowledge (print concepts) is about being exposed to a variety of texts like storybooks, novels, fiction and nonfiction, myths and legends from different cultures and countries, fables, poems, newspapers articles and recipes. It also includes rules of print such as, right to left punctuation. When all strands of language comprehension are being taught the reader is developing and using skills to help them get to meaning and comprehension. As the reader improves their language comprehension they are becoming increasingly strategic in their use of these skills.

Understanding the rope helps us see where and why our dyslexic children are struggling and where our children’s gaps are. It also helps us see why using a Structured Literacy approach is crucial. To learn more please read the document called ‘What is Structured Literacy?‘.

A short video of Scarborough’s Reading Rope:

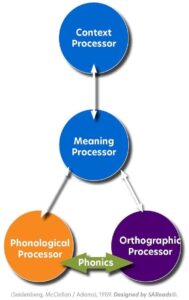

How does the brain process all this information?

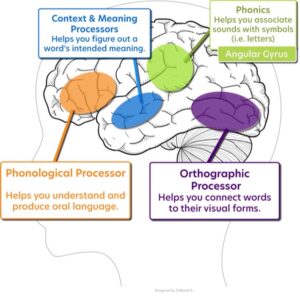

The Science of Reading research has provided us with what skills we need to teach and how we teach them, but it has also provided us with how the brain processes the information. The Four-Part Processor was originally proposed by Seidenberg and McClelland (1989).

This diagram above shows how we connect our speech (what we hear) to print (what we write) and print what we write to speech (what we hear).

When you want to spell a word we hear the word and process its parts in the phonological processor but to write that word we need to link each sound to its letter (from the orthographic processor) and record those letters.

When we read a word, we see the letters and process these in the orthographic processor and make a connection across to the phonological processor to be able to pronounce the sounds and blend to make the word.

We are going to use the sounds b/a/t/ as an example. Once we have learned the sounds b/a/t we use phonics/alphabetic principle to process this information in our orthographic processor to map/master the letters BAT for reading, spelling and writing. This is where we are mapping the sounds to the letters which then move to the sight word memory (also known as orthographic lexicon and letterbox) from the orthographic processor.

We now have our word BAT and we need to work out which bat is being referred to: bat as in cricket bat or the bat as in the flying animal? This is when you are using your meaning processor. We use our context processor to help with this. The sentence in which the word bat is being used is: ‘The bat has wings and flies.’ In the context of this sentence we can figure out which bat is being referred to.

You will notice the arrows are going in both directions, this is because we process the information in both directions. All the connections in the brain need to work for your child to read and comprehend the text they are reading. This also means both parts of the rope are equally important and both NEED to be taught.

The majority of schools in New Zealand teach literacy using the approach called the Three Cueing System also referred to as MSV (Meaning, Semantics and Visual Cues) or a Balanced Literacy approach. We have gone into more detail explaining MSV/Balanced Literacy in the section called ‘Why can’t my child read?‘ Understanding how our brains process the information when reading will help explain why your child can’t read.

This video explains the Four-Part Processor and the Three Cueing System/MSV approach, and how one uses all the skills of the rope and the other only uses parts of the rope – The Trouble with the Three Cueing System

Please also refer to this article from Massey University’s Dr Chrissie Braid – ‘Getting it, Not Guessing It: Addressing the 3 Cues.’

The Four-Part Processor has helped us understand our ‘Why’ questions – ‘Why isn’t my son learning to read?’, ‘Why did his brother learn to read ok?’ As parents these are questions we ask ourselves a lot – ‘Why can’t my child read?’ The diagram and explanation above helped us see how all the parts of the brain connect and work together and if those arrows are not connecting then we could see where the difficulty was happening. This is why we have chosen to add this diagram.

We added this brain image because it helped us see where processors are located in the brain and the geek in us likes it!

Extra Learning

Laura Stewart from the Reading League has written an exceptional white paper on The Science of Reading and it goes deeper into the understanding and research than we have. Access it here The Science of Reading – Reading League

For those who would like to learn even more about The Science of Reading and what we have learned from it, please head to our ‘Learning Hub‘ where we list many webinars, articles and podcasts. We have also created a ‘Glossary‘ of words to help with the terminology used throughout the website.

Thank You

We would like to thank Dr Chrissy Braid from Massey University and Jodi Clements from the Australian Dyslexia Association for their time, support and advice in writing this document.

This document was created by Sharon Scurr, founder of the deb, December 2021.